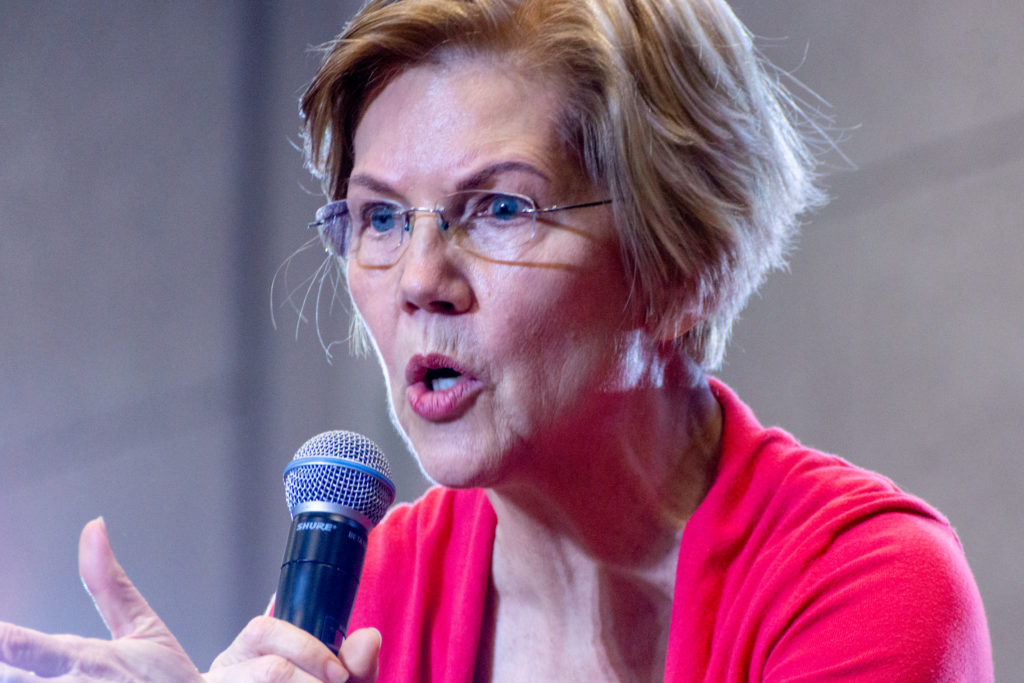

Update, March 5, 2020: Elizabeth Warren has ended her presidential campaign.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., who leapt out in front of other heavyweight Democratic presidential hopefuls by forming an exploratory committee on Dec. 31, has blazed the campaign trail with immediate stops in Iowa and New Hampshire.

Warren, her state’s senior U.S. senator and a Harvard Law School professor emerita, regularly reinforces her distrust of billionaires and bankers — notably President Donald Trump, who routinely refers to Warren as “Pocahontas” in reference to an ongoing flap over the nature and extent of her Native American heritage.

“If Democrats are going to win and make real change, we’ve got to build a movement, and that happens at the grass roots,” Warren recently told The Atlantic. “It doesn’t happen from super PACs or self-funding billionaires or corporate money. It happens because we built it one person, one $10 contribution at a time all across this country.”

Warren, 69, has positioned herself as an expert on the financial industry — and she drew that industry’s ire in the aftermath of the Great Recession when she advised President Barack Obama’s administration on the formation of a consumer protection bureau. Some also argue Warren has used her political savvy to financially outsmart her would-be competitors.

Here’s more on Warren’s political and financial history:

- Like any other federal political candidate, Warren has been limited in the amount of money she can collect from individual donors. But she nonetheless has raised $34.7 million since 2013 — more than half of which came from donors giving less than $200. She still has $12.5 million in her U.S. Senate campaign account, which she can use toward her presidential bid.

- Warren’s minimum net worth (minus the value of her residence) was estimated to be $4.6 million in 2017, according to financial disclosures Warren filed with the U.S. Senate. However, because senators are required to report their assets in ranges, her income could be as high as $10.6 million. She and her husband, Bruce Mann, reported an income of $913,000 in 2017, according to Newsweek. (Update, Feb. 5, 2019: Warren has filed a presidential candidate personal financial disclosure that indicates she’s earned royalties from book sales, maintains her seven-figure wealth largely in garden-variety bond and mutual funds and retains her title as “emeritus professor” at Harvard University.)

- In a Jan. 2 interview with MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow, Warren fired a warning shot to billionaires who could potentially self-fund their presidential campaigns. The wealthy, she said, “have bought the government they want.” At the time, billionaires Michael Bloomberg and Tom Steyer were rumored to be in the Democratic mix. Nine days later, Steyer announced he would not seek the Democratic nomination, and Bloomberg has yet to make a public announcement about his candidacy.

- Unlike Obama and former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, the previous two Democrats to contend for the White House, Warren has shunned super PACs as a funding mechanism. Super PACs can raise and spend unlimited amounts supporting or opposing candidates. One caveat for Warren: If a super PAC (or super PACs) form to support Warren against her wishes, there’s little she can do to stop them, other than ask them to shut down or urge her supporters not to donate. Legally and by definition, super PACs operate independently from campaign committees — even if some super PACs are run by friends or former staffers of the politicians they support.

- Warren, who was a registered Republican as recently as the mid-1990s, is one of seven senators who have pledged not to accept money from corporate political action committees, according to Washington, D.C.-based interest group End Citizens United. But she and others have been criticized for not going far enough. And Warren doesn’t reject all PACs: She operated her own, PAC for a Level Playing Field, a leadership PAC that until 2017 accepted tens of thousands of dollars from political action committees affiliated with labor unions. (Some of the money her leadership PAC recently gave to Democrats went to potential competitors for the Democratic presidential nomination, including Sens. Kamala Harris, Kirsten Gillibrand and Amy Klobuchar.)

- Warren was one of five confirmed or potential Democratic presidential contenders who received more than half their contributions in 2017 and 2018 from women, according to a Center for Public Integrity analysis of data from ActBlue.

- Ahead of the 2018 midterm elections, Warren carved out space in her own U.S. Senate campaign headquarters for a “shadow war room” aimed at electing Democrats across the country, and she helped raise about $8 million for other candidates and committees in 2017 and 2018. According to the Washington Post, party operatives believe she was building a massive network — especially in states with early presidential primaries or caucuses — that she can now leverage as a presidential contender.

- In the throes of last year’s midterm election, Warren was the third-highest spender on digital ads — behind only President Donald Trump and former Rep. Beto O’Rourke, a Democrat who was in a close race for the seat occupied by incumbent Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas. While Trump has been officially running for re-election since the day of his inauguration, and O’Rourke was in the midst of a historically expensive U.S. Senate race, Warren’s re-election bid was not competitive.

- Eighty-nine Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives signed a letter urging then-President Obama to tap Warren to head the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, an agency she helped create from scratch in the aftermath of the Great Recession. Others petitioned the president to pick Warren, too, but he ultimately nominated Richard Cordray — a man Warren herself had picked to join the staff of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau when she was helping hire its 500 employees.

Sources: Center for Public Integrity reporting; OpenSecrets.org, Federal Election Commission, Vanity Fair, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Huffington Post, End Citizens United, New York Times, MSNBC, Newsweek, Boston.com, The Intercept, Time.com, ABC News, Argus Leader.